Vela Projects is proud to present It’s Not Going to Get Better, Thero Makepe's debut gallery exhibition. It’s Not Going to Get Better is crafted as response to a wave of global electoral fever. 2024 was a year which saw more than 100 countries, and approximately half of the world’s population, heading to national polls. Focusing on the Botswana General Elections, Makepe interprets the tenor on the ground of a country that is often held as the poster child of a peaceful African democracy. Despite promises of freedom and opportunity, in this late-capitalist moment, the lead-up to the election seemed bleak.

The exhibition title, drawn from “Remorseless,” a rap song by Billy Woods, explores the pessimism and disillusionment of Millennials and Gen Z who, as so-called ‘born frees,’ have been promised a better life and upward mobility. Makepe seeks to capture a mood that reflects the murky and shifting nature of the oppression faced by younger generations.

In the words of Lee Chan Dong, the Korean film director of Burning (2018), one of the cinematic inspirations for the show, “There is an ambiguity in the world we live in that seems to reflect no clear answer to the questions we have today. I feel like young people have realized that there’s something wrong in this world, but it’s very difficult to figure out exactly what is causing the problems and what lies underneath.”

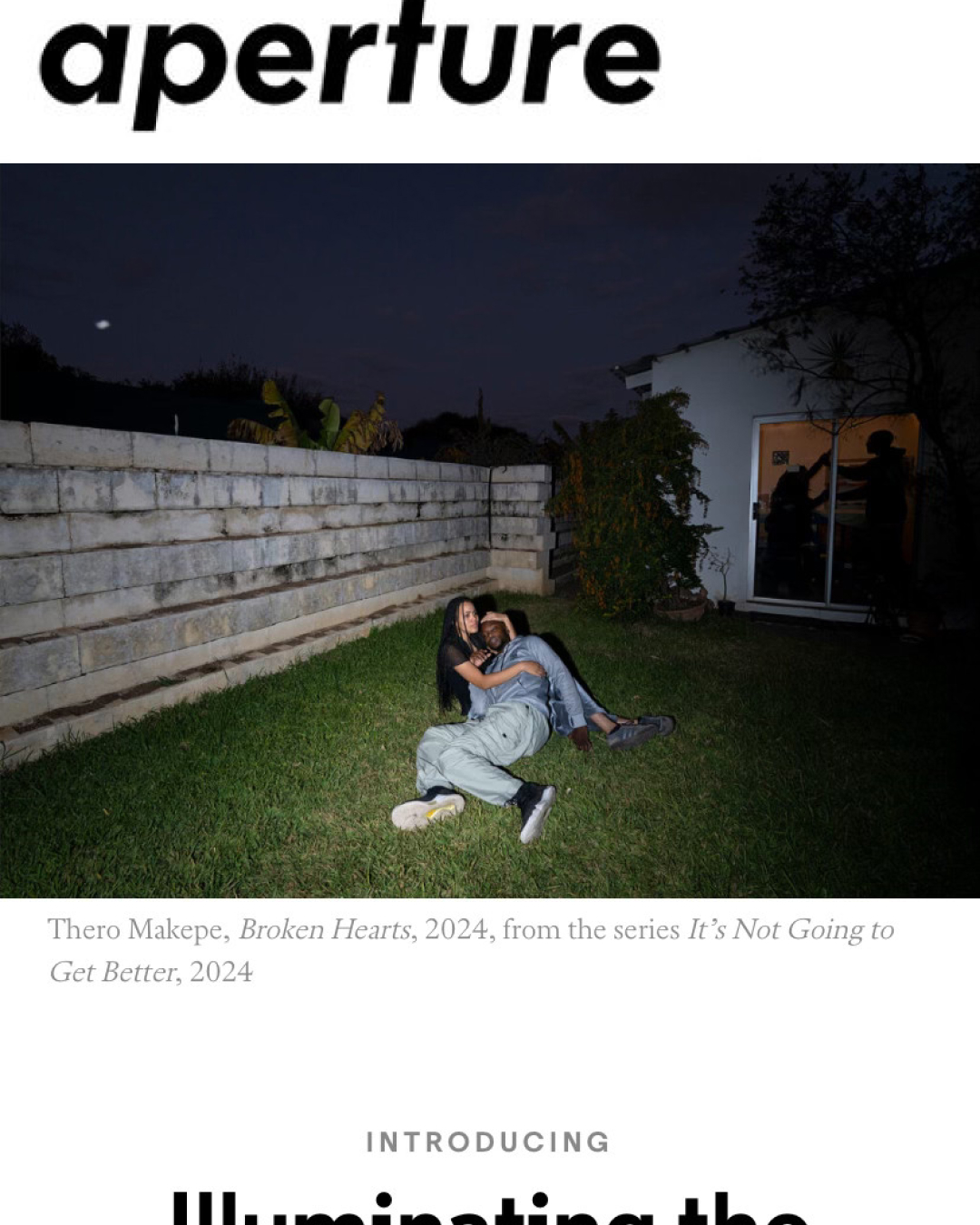

Throughout this exhibition, Makepe pursues a constructed mode of image-making⎯a style he developed during previous bodies of work such as Fly Machine/Mogaka (2018) and We Didn’t Choose to be Born Here (2020–2022). Much like a painter ‘creating something out of thin air,’ Makepe enjoys staging tableaux that support his narratives, existing deliberately in the ambiguous space between documentary and fiction. These scenes draw from the everyday experiences of life in the city, but they seem heightened, amplifying the underlying sense of tension and unease.

His figures often appear in moments of stasis, suggesting a lethargy born from despondence. For instance, in the image entitled Mokgokolosa (2024), which translates as A Downward Slope, a man is seated behind a drum set. His eyes are downturned, eyes, his hands are folded in his lap, and he is surrounded by everyday objects. Despite being too old for teenage dreams of stardom, behind him burglar bars are spread out in a starburst above his head. Part saint, part martyr, he appears to be waiting for something to happen.

In the image Re Mmogo Akere? (We are together, right?) (2024) a man stumbles on the sidewalk at sunset while, nearby, another man is fixated by his smartphone. This staging may reflect a sense of limbo or entrapment that is often felt by people who live local lives but are simultaneously engaged in a constant intermeshing of global culture, news, and social concerns. As Makepe aptly observes:

We are participants and bystanders at the same time. There’s a conundrum of being concerned about international affairs while ignoring the pertinent issues right in front of you.

In the contemporary world, we are able to connect with and respond to news and information from all over the globe, but attention to our immediate environment becomes diverted. We are immobilized with choice and consumption at the cost of social life. To quote Lee Chang Dong once more, “It seems that the world we live in continues to become more and more sophisticated, convenient and cool on the outside, but there are so many problems underneath that we can’t really discern.”

A consequence of this context is a pervasive shift from communalism to individualism that Makepe explores throughout the show in works such as Moral Compass (2024). The scornful expression on the finely dressed woman in the foreground seems to suggest that even the elite are not at ease. Whilst this shift may be felt worldwide, Makepe argues that it is particularly resonant within the African continent:

During pre-colonial Africa and even during the liberation struggles on the continent, there were collective goals that people organized towards. But now, that's not the case; problems are more individualized. Because the problems are trapped within individuals, people are far more isolated and prone to nihilism.

In response, Makepe emphasises the collaborative nature of his practice. He uses family and close friends as models and will tap into their experiences, stories, and memories. In his words:

Whilst some images I make are highly staged or fictional, others are more rooted in reality, as I photograph people I know personally in situations they find themselves in regularly. In either scenario, the subjects of my images are conduits for broader social contexts in Botswana that relate to their social class, gender, or age.

One may consider Modimo a mo Tlamele (2024), which Makepe shot with the assistance of his uncle. An elderly man stands with his hands clasped in front of his tucked shirt, a single crutch hangs from his right forearm, and his eyes are closed. The title, which translated means God Protect Them, has a somber yet defiant tone. Despite appearing to be in pain, a warm glow lights one side of the man’s face, suggestive of the divine, while he is placed in the quietness of a cleanly swept pavement at sunset.

Makepe’s images, sometimes quiet, sometimes dominating, show the lives of everyday people and depict scenes that are indeed beautiful, but remain tragic and problematic. The scrutiny of Makepe’s lens makes us consider the lives we live. Rather than condemnation, Makepe’s photographs ask that we take the time to look at the lives of those around us, both known and unknown.

In relation to his home country, Makepe seeks to expand a contextual understanding of Botswana. He hopes to offer a counter-narrative for a country which seems to be predominantly depicted for its wildlife, natural beauty, and rural culture. Despite this, there is, for Makepe, a sense of emptiness and alienation within its urban life. Through his lens as an auteur, Makepe provokes:

I don’t aim to provide solutions, but I ask why things will not get better... Ultimately, it's not clear exactly how to move forward; it's all a mystery, and that's what's central to my work.

Now, at the end of 2024, the pessimism of the title may seem particularly piercing. Botswana’s elections delivered an unprecedented defeat of the ruling party that has governed in Botswana since the country’s independence 58 years ago. It was a landslide victory for Dumo Boko, aged 54, for whom young voters made up about a third of the more than one million people registered to vote in the arid and sparsely populated country.

Even Makepe is hopeful that this change may bring marginal gains in freedom of expression, voter suppression, and political engagement amongst a population that he describes as more passive that those of its neighbours in Southern Africa. Still, it is a future which, at best, remains unclear.